Both unable to find "Zur Frage der Übersetzungskunst" and unable to ignore Friedrich's missing analysis of "Sonnet IV" by Louise Labé, I went off in search of the original poem and meanwhile came across some interesting translations.

I had to refresh my memory on French poetry (days of counting and miscounting syllables in French sonnets still haunt me) and fortunately Labé's "Sonnet IV" is pretty straightforward. It is a Petrarchan (Italian) sonnet, thus consisting of eight lines (two quatrains) of proposition followed by six lines (two tercets) of resolution, following the rhyme scheme abba, abba, ccd, eed. Each line consists of ten syllables.* Additionally, French Petrarchan sonnets contained césures mid-way through each line, 5-5 syllables, 4-6 or 6-4.

Louise Labé was a French poet of the 16th century, the daughter of a rope-maker, who also went by the name La Belle Cordière. There is some scholarship that posits she – and her poetry – was a creation of various French poets in her native Lyon.

While reading these translations and with an air toward divining Friedrich's potential commentary, keep in mind these all-encompassing, philosophically-inspired questions pertaining to translation that he brought up early on:

• Is translation something that concerns the cultural interaction of an entire nation with another? • Is translation just the reaction of one writer to another? • Does translation resurrect and revitalize a forgotten work, or does it just keep a work alive to satisfy tradition? • Does translation distort the foreign in an old work under the pressure of specific contemporary aesthetic views? • Do translators pay close attention to the differences inherent in language or do they ignore them? • Does the translation create levels of meaning that were not necessarily visible in the original text so that the translated text reaches a higher level of aesthetic existence? • What is the relationship between translation and interpretation: when do the two meet and when does translation follow its own laws?

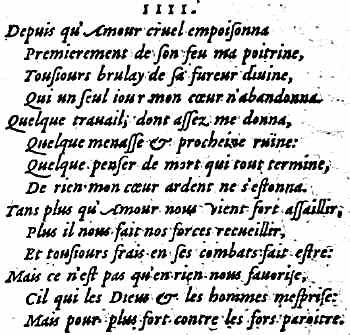

Depuis qu'Amour cruel empoisonna

Premièrement de son feu ma poitrine,

Toujours brûlai de sa fureur divine,

Qui un seul jour mon coeur n'abandonna.

Quelque travail, dont assez me donna,

Quelque menace et prochaine ruine,

Quelque penser de mort qui tout termine,

De rien mon coeur ardent ne s'étonna.

Tant plus qu'Amour nous vient fort assaillir,

Plus il nous fait nos forces recueillir,

Et toujours frais en ses combats fait être;

Mais ce n'est pas qu'en rien nous favorise,

Cil qui les Dieux et les hommes méprise,

Mais pour plus fort contre les forts paraître.

If you look closely, you'll likely notice that this is actually a re-writing of the Old French version – e.g., méprise vs. mesprise.

Translated by: Peter Low

Since first cruel Eros poisoned me with fire,

piercing my breast and kindling passion in it,

I’ve burnt with a god-sent frenzy of desire

that has not left me for a single minute.

No tortures - and I’ve felt enough of those! -

no threats that my whole world would fall apart,

not even thoughts of death’s eternal close,

nothing could cool the ardour of my heart.

The more that god assails us hard and long,

the more he makes us sturdier and braver -

we’re really at our freshest in these battles.

But this he does never as grace or favour

(he only knows contempt for gods and mortals):

it’s just to prove he’s stronger than the strong.

Perhaps in an effort to mimic some of the feminine rhymes of Labé's b lines, Low integrates feminine rhymes into his first quatrain: "in it" and "minute" is successful; "with fire" and "desire" not so much. However – again – my knowledge of feminine rhymes is limited. The first line, in fact, has only ten syllables, thus preventing it from being an accurate feminine rhyme at all. In general, Low has chosen not to follow Labé's rhyme scheme, electing instead abab cdcd efg hie or possibly hge? Style aside, in the first quatrain alone, Low replaces "Amour" with "Eros," reiterates the "fire" theme – Labé's "feu" becomes "fire" and inspires the gerund "kindling" –, and the frenzy or "fureur" that has not left her for a day – "un jour" –, now has not left her for even a "minute." This certainly has to be one of the "new levels of meaning" Friedrich talks about. The Labé I picture from the French is less active and more resigned. She tells herself to buck up and carry on because daily she feels a lingering passion. If she felt it every minute, I think this would be a very different poem.

Translated by: James Kirkup

Ever since Love first

darted poison in my breast,

his divine fury

- never cast out from my heart -

never ceases to burn me.

And however much

I tried, and however hard,

even menaced by

impending ruin, the thoughts

of death, that ends all, never

struck my ardent heart.

- The more Love comes to Plague us

the more we must build

powers of stiff resistance

to fight his battles always

with renewed vigour.

Yet we are not without aid -

He who despises

both God and his fellow men

appears stronger than the strong.

I got this from the same website that supplied me with Peter Low's translation. Kirkup has elected to translate Labé's sonnet into a Japanese-English tanka (is it actually a Japanese tanka if it's in English?). The tanka is an ancient Japanese poetry form consisting of five lines, with the syllabic patterns, 5-7-5-7-7. What would have impressed me most about this, would have been if the development and prevalence of the tanka had occurred around the same time as the development of Petrarch's sonnet form. Alas, it's anywhere from a couple hundred to six hundred years off. What a tanka does bring to the English translation is the foreign element. From Friedrich's remarks at the end of his chapter in Theories of Translation, I think it's possible to classify this translation as an over-elevated work. It over exoticizes a French sonnet into a 7th century Japanese tanka, interpreted through English eyes. However, much as the form startles me (you could say it "distort[s] the foreign in an old work under the pressure of specific contemporary aesthetic views"), I think Kirkup captures the meaning very well. A line like "De rien mon coeur ardent ne s'étonna" doesn't have a good, word-for-word English translation and the verb "s'étonner" – literally, "to be surprised" or shocked – turns up in various completely different forms, as in: "cool" from "nothing could cool the ardour of my heart" (Low); "struck" from "death, that ends all, never/struck my ardent heart" (Kirkup); "make no move" from "And so I sigh although I make no move" (Park); and – Brownie point award goes to – "war niemals überrascht" from "mein Herz in Glut war niemals überrascht" (Rilke). Many congratulations to Rilke for managing to use the verb "überraschen," which means, of course, "to surprise."

Translated by: Alice Park

When Love arrives, I hide myself away,

Though filled by burning torments of desire,

That scorch and sear and scar my breast with fire,

And flames devour my heart both night and day.

O how I feel the harsh travails of Love!

The wounds and devastating dreams of death

Descend on me whenever I draw breath,

And so I sigh although I make no move.

The more Love comes, the more I am besieged.

I gather up my forces, yet I fear

The crack in my defenses may be fatal.

O archer Love, who scorns both gods and mortals,

You draw your bow and aim your shafts for all,

Then stab our hearts despite our fortress walls.

Park has obviously attempted to replicate Labé's rhyme scheme more so than Low or Kirkup. The octave is comprised of an abba cddc pattern which, considering the comparative shortage of rhyming words in English, is an understandable deviation from Labé's abba abba. After all, English doesn't have the luxury of all those matching verb endings. However, what we are confronted with, again, is an alteration of, if not the "meaning," that which is explicitly stated in the original sonnet. Labé makes no mentions of Love's continuous arrival. Park's translation could easily be interpreted in such a way as to suggest that the narrator is often plagued by and singled out by Love. "When Love comes, I hide myself away." I would hide myself away, too, if I had a persistent divine guest poisoning my breast with his fire. But Labé's poem doesn't talk about this at all. In fact, if anything, the poem says that we must be steadfast against the labors Love sends our way, matching his challenges with fresh fight. A good deal of Park's poem deviates from Labé's content. It reminds me of the way Malherbe filled out Seneca's Lucilius letters, changing the short, unconnected style, to long, flowing prose with ample description.

Translated by: Rainer Maria Rilke

Seitdem der Gott zuerst das ungeheuer

glühende Gift** in meine Brust mir sandte,

verging kein Tag, da ich davon nicht brannte

und dastand, innen voll von seinem Feuer.

Ob er mit Drohungen nach mir gehascht,

mir Mühsal auflud, mehr als nötig, oder

mir zeigte, wie es endet: Tod und Moder –,

mein Herz in Glut war niemals überrascht.

Je mehr der Gott uns zusetzt, desto mehr

sind unsre Kräfte unser. Wir verdingen

nach jedem Kampf uns besser als vorher.

Der uns und Göttern übermag, ist denen

Geprüften nicht ganz schlecht: er will sie zwingen,

sich an den Starken stärker aufzulehnen.

I don't speak, read, or write German. I recognize words like seitdem, Gott, Tag, ich, Feuer, etc. so I obviously can't provide any substantial commentary on Rilke's translation. I can, though, deduce that the rhyme scheme is significantly closer than any of the other translations I found – abba cddc efe gfg –, that words like überrascht are better choices than "I make no move" (the complete opposite of transitivity!), and that – most importantly of all – this is a translation of Labé's Sonnet IV. Skillful. However, I suppose that this actually puts me back at square one with Friedrich's speech. Just what would he say about this?

*(In theory. If someone with better French poetry skills than mine could point out to me how these lines contain ten syllables, I would be much obliged: "Plus il nous fait nos forces recueillir" and "Cil que les dieux et les hommes méprise." Fortunately, these two lines occur [intentionally?] in analogous places, but by my calculation they only contain nine syllables. Can one say "homm-es" and "forc-es"?)

** Doubtless "Gift" is my favorite faux ami of all time. It means "poison."